This year marks the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, which, if you know my work, I have a strong personal relationship with.

As you’re no doubt already aware, my connection to the storm and the experiences of the people of New Orleans all stemmed from seeing the disaster unfold on TV from my home in Brooklyn. Long story short, I ended up volunteering with the American Red Cross, was trained as a disaster-response worker, and deployed to Biloxi, Mississippi, just 90 miles from New Orleans.

My three weeks as a volunteer there, where I also blogged about my experiences, led to the self-published zine Katrina Came Calling, and, some time later, to the “nonfiction graphic novel” A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge. I first created A.D. in 2007–2008, profiling a cross-section of New Orleans residents who survived Katrina and the subsequent flooding. It was originally serialized online at Smith Magazine, and later expanded into a New York Times-bestselling book from Pantheon, published in 2009.

One of the first widely read works of comics journalism, A.D. became a bestseller, appeared on numerous best-of-the-year lists, and has since been taught in classrooms across the country. It continues to spark conversations about systemic inequality, race, resilience, government accountability, and the comics form itself.

So now here we are in 2025, taking a moment to reflect on the disaster’s legacy and its place in our national memory.

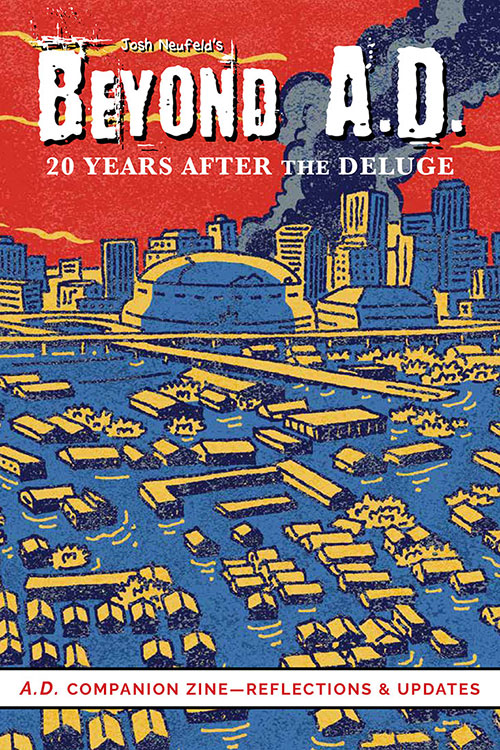

To mark the occasion, I’ve put together Beyond A.D.: 20 Years After the Deluge—a collection of updates and reflections on A.D. This “companion zine” brings together follow-up stories, related comics and illustrations, and previously unseen artwork connected to A.D. (Beyond A.D. is 24 pages, full color, and sells for $10. I’ll have copies at the Small Press Expo, in Bethesda, Maryland, September 13–14, 2025.)

Two decades on, what was once journalism is now history. In today’s era of escalating climate disasters and persistent questions about equity and truth, I strongly feel that the themes of A.D. remain urgent. And, apparently, the leaders of Louisiana State University’s honors college agree, because they’ve invited me to LSU to present A.D. to their incoming freshman class. I’ll be traveling to Baton Rouge on Sunday, staying for three days to deliver a convocation address, meet with students, and answer questions from various classes that have been studying the book. I’m excited to present A.D.—and the stories of Denise, Leo & Michelle, Hamid & Mansell, Kwame, and the Doctor—to a whole new generation of students—none of whom were alive when Katrina happened!

Because of the anniversary, A.D. has been back in the spotlight again, and there’s been some new press coverage. Here’s a roundup:

- In May, Forces of Geek reviewed the book, calling it “a remarkable piece of work.”

- Larry Smith, erstwhile editor of SMITH, looked back on the creation and publication of the A.D. webcomic in a Substack post (that also features the hardcover and some interior images).

- I was interviewed on the Louisiana Anthology Podcast, a long-running effort by scholars Bruce Magee and Stephen Payne. As its title suggests, the weekly podcast is a real deep dive into the Pelican State, with regular features including “This Week in Louisiana History,” “This Week in New Orleans History,” as well as promotions of recent and upcoming events like “This Week in Louisiana” and “Postcards from Louisiana.” The podcast featured me in two consecutive episodes leading up to the Katrina anniversary. We talked quite a bit about A.D., the catastrophic flooding, and my upcoming visit to LSU. (In fact, the son of one of the hosts is a freshman student at LSU, so he appeared on the pod as well.) Here are links to my first episode and the second one.

- Last but not least, I was interviewed by Dave Cowen for his blog SerioComics. He asked me a lot of multilayered questions—not only about A.D. but my other work as well (including Beyond A.D.)—and I tried to provide multilayered answers! You can check out the exchange here.

As I write in Beyond A.D., this feels like the moment not just to look back on Katrina and the many governmental failures that really made it a disaster, but to recommit—to remembering, to resisting, to rebuilding. Defend New Orleans!